SURROUND SOUND: Field Report from Leimert Park

A progress update on building tools for collective memory

The music playing outside Lore Bookstore wasn’t part of our event. It was Leimert Park’s weekly art walk, soundtrack bleeding through the walls into our gallery space. But one attendee made a connection I hadn’t seen: she linked the sound outside to a clip from the SURROUND SOUND processor showing the 1971 Watts Festival, noting how music became the medium for collective healing then and now. Fifty years collapsed into a single moment of recognition. These are exactly the connections I am seeking to bring worlds together.

This is a progress report on a year-long experiment in building tools for collective memory. But it’s also an attempt to share the methodology I’m developing—not just the output. If you’re working on similar questions about archives, community engagement, or creating conditions for connection, consider this an invitation to investigate alongside me.

For the past year, I’ve been developing SURROUND SOUND — a project that started during my 2024 residency at the UCLA Film & Television Archive, where I worked with thousands of hours of KTLA newsreels documenting LA from the 1960s-1990s. The archive captured a city in constant transformation: displacement, organized abandonment, community resistance, moments of joy between the cracks of crisis. But I kept noticing something the official record missed: the micro-performances of people under the eye of the camera. The side glances. The shade. The subtle refusals of the story the news was trying to tell about them.

I wanted to build something that could surface those moments and connect them across time and geography, creating alternate pathways through the archive that the original producers never intended.

The Processor: Building Semantic Links Through Performance

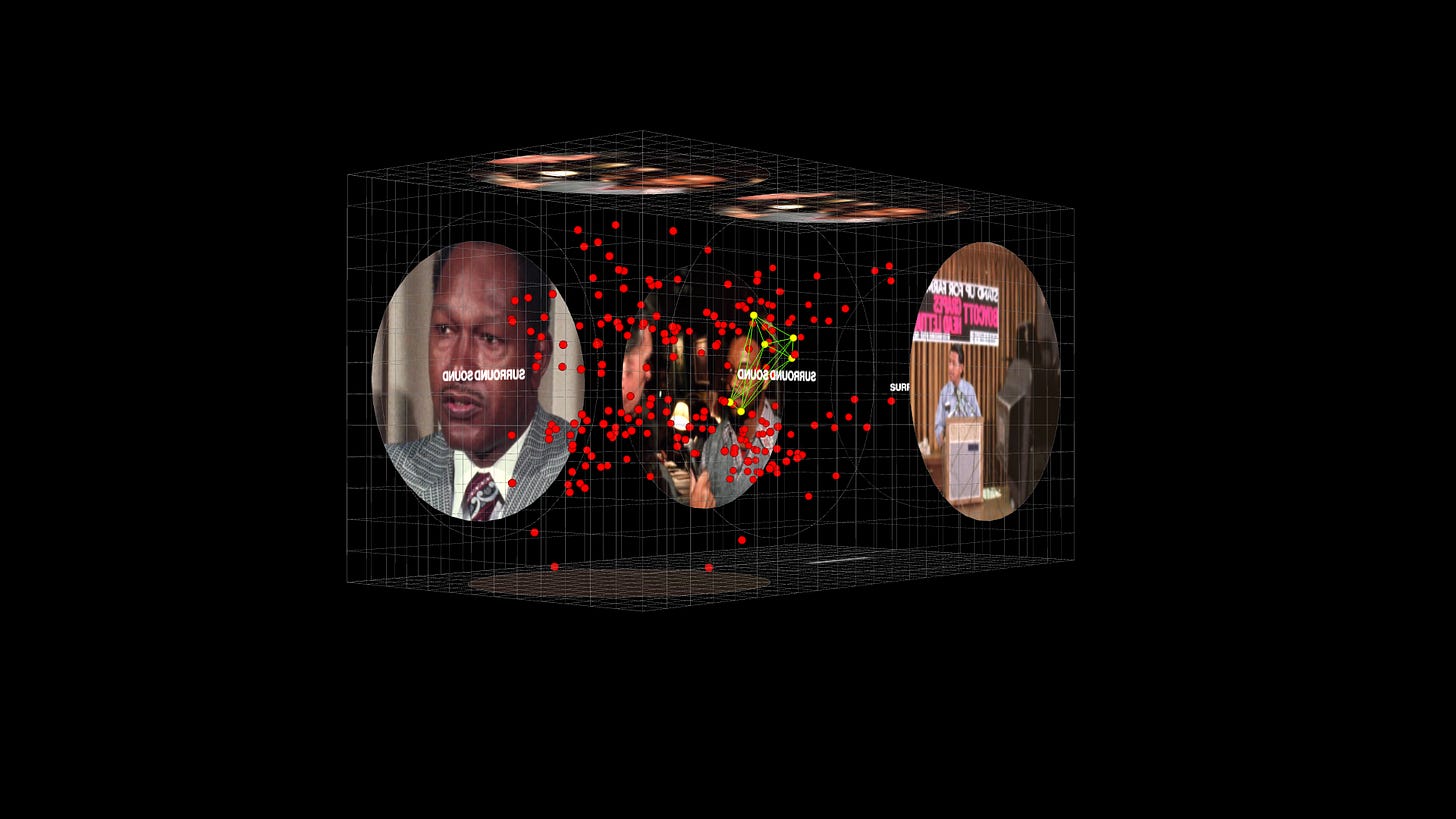

The SURROUND SOUND processor is an interactive 3D environment — a rectangular container that serves as both television (the box that brought images into living rooms) and cage (the frame that tries to contain subjects within a particular narrative). Inside this container, archival clips float as nodes in a semantic field, attracting and repelling each other based on machine learning analysis of the footage itself.

Here’s how it works technically: I used computer vision, metadata scraping, and audio analysis to generate vector embeddings for each clip, capturing not just what’s explicitly said or shown, but the affective qualities — detected emotion, body language, vocal tone, the material texture of the performances themselves. A Latina woman’s expression in the 1970s might link to another Latina woman’s expression in the 1980s. A police commissioner’s anger bleeds into a mayor’s anger, which gives way to community protesters’ anger. These connections aren’t about equating the clips or flattening their contexts, but about tracing simultaneity — how these stories of displacement, resistance, and survival were emerging across different LA neighborhoods within roughly the same period.

The processor is designed to be navigated by users. You can fly through the 3D space, select individual nodes, let the machine generate pathways on its own, or control the “noisiness” of the output (how long it lingers on one story, how many clips play simultaneously). I’m interested in creating a space where those dispossessed by these systems might find each other across time.

This is what I mean by the commons: not just shared resources, but shared experience of systemic failure and the collective practices emerging in response.

Virtual Machines: Testing in Community

On September 28th, I finally got to show the processor publicly at Virtual Machines, a one-night group show I co-hosted with artists Miela Foster, Natalie Brewster, Theo Hargis, and Izaiah ZayZay + the SBS Quartet at Lore Bookstore in Leimert Park. The event centered on self-expression as a tool of flight within systems of constraint — Miela’s paintings, Theo’s paintings, the quartet’s music, Natalie’s talk on self-expression, and my processor all in conversation.

The location mattered deeply. Lore sits in the building that once housed the iconic Brockman Gallery, a stronghold for Black artists in a neighborhood that has long been the West Coast epicenter for Black creativity. Leimert Park itself emerged as a hub for Black culture after the Watts Rebellion, when the once-segregated, white-only subdivision transformed during white flight into a bastion for emerging Black creatives and aspirational Black middle-class homeownership.

While Leimert Park isn’t directly represented in the KTLA archive I’m working with, I showed clips connected to nearby Watts — footage of community rebuilding efforts against the grain of the police state’s devastation. Several attendees noted connections between past and present throughout the evening, like the music parallel I mentioned at the start.

Learning from Ben Caldwell: What Sustained Engagement Looks Like

Before the event, I had the privilege of visiting Ben Caldwell at KAOS Network, the community center he’s run in Leimert Park since the 1980s. Caldwell is a video artist, community organizer, and what he calls an “incubator” for community ideas. When Metro announced the expansion of the Crenshaw Line into Leimert Park, Caldwell and other community leaders worked to fight off gentrification by embedding culturally significant symbols into the new plaza design. His Sankofa City project uses technology — autonomous cars, repurposed pay phones, interactive infrastructure — to make Black history and culture accessible in everyday life, designing public space with the community as the starting point rather than an afterthought.

During my half-hour at KAOS, I watched a revolving door of neighbors, business owners, and creatives stop by to soak in the wisdom of a space filled with prototypes.

The Artist’s Dilemma: Who Benefits from the Work?

I’m deeply aware of my position as someone from outside Leimert Park hosting an event there for one evening. Throughout the planning process, I developed a practice of deeply researching communities before entering, connecting with community stewards and current events to understand the challenges and opportunities within each neighborhood. Leimert Park, like many historic neighborhoods around LA, faces real threats of gentrification. And art institutions and artists themselves often serve as the vanguard of gentrification waves — identifying “development opportunities” and making neighborhoods more desirable for people not originally from there.

The Black Owned and Operated Community Land Trust, led by entrepreneurs like Tony Jolly and Akil West, is working to protect local businesses from displacement by establishing Black ownership of the commercial buildings that have marked the community for decades. Their model shows what’s possible when communities control their own development.

But what’s my role in all this? I’m asking this question seriously. I don’t want SURROUND SOUND to be extractive — showing up, collecting stories, and leaving. It’s much more important for this work to begin way before each event and continue afterward. I’m treating each venue and its particularities as an opportunity to come into community with people already doing the work to preserve their neighborhoods, to offer up my tools as a resource, and to know when to sit, learn, and support rather than lead.

This is where I need your wisdom. If you’re working at the intersection of art and community — or navigating questions of extraction vs. contribution from any discipline— how do you approach this? What frameworks guide you? What mistakes have you learned from?

Drop your thoughts in the comments. I’m building a resource library of approaches to this question, and I’ll share what I learn in a future post.

What I’m Learning: A Method for Ethical Engagement

Through this process, I’m developing a framework that others might find useful. It’s still rough, still forming, but here’s what’s emerging:

Before entering a community:

Spend time understanding its history and current pressures (for Leimert Park: the Metro expansion, gentrification threats, the land trust’s work)

Research who’s already doing the work (like Ben Caldwell at KAOS, the Black Owned and Operated Community Land Trust)

Ask yourself: What resources can I bring vs. what do I need to learn?

Connect with community stewards before showing up with an idea

During the event:

Design for co-investigation, not performance (the processor becomes a tool for attendees to explore together)

Create space for lateral connections (people finding each other, not just responding to your work)

Stay present to what emerges vs. clinging to what you planned (like the attendee’s music connection I hadn’t seen)

Listen to what the community sees in the work that you don’t

After the event:

Follow up with collaborators and attendees (don’t just disappear)

Document what the community taught you, not just what you showed them

Stay in relationship beyond the single event

Ask how the work can continue to be useful

This is an evolving practice rather than a solution. And honestly, I’m still figuring out how to do this well. If you’re navigating similar questions about working across communities, I’d love to know what frameworks guide your practice.

Building Together

The processor is still evolving. Each event teaches me something new — often from attendees who see connections I missed or ask questions that reshape how I think about the tool.

Immediate next steps:

Continuing the SURROUND SOUND tour across LA neighborhoods (each with its own history, its own stewards, its own questions)

Developing tools through my UCLA Social Software cohort that will let communities not just access and annotate the archival newsreels, but submit their own counter-memories — the stories that never made the official record

Testing methods for making documentation collaborative rather than extractive, where the process of archiving becomes a practice of collective memory-making

Where you come in:

This work gets better with more perspectives, more contexts, more people testing these methods in their own communities. The goal is to build decentralized infrastructure for collective memory — not a single tool I control, but a set of practices others can adapt. I’m learning that the most important connections often come from the community itself, not from the machine or from me.

More to come.

How to Participate

There are multiple ways to engage with this work, depending on your capacity and interest:

If you’re just curious:

Drop a comment below sharing one connection you see between past and present in your own neighborhood or community. What histories are you noticing that the official record missed?

If you know of venues:

I’m building a list of LA communities and spaces that might host SURROUND SOUND events. Reply with: [Neighborhood] + [Venue name] + [Why it matters to that community]. Let’s map the city together.

If you’re navigating similar tensions:

Working with art, archives, technology, and community organizing? Wrestling with questions about extraction vs. contribution? DM me or reply here. Let’s learn from each other’s frameworks and mistakes.

If you want to contribute signals:

I’m collecting signals around: moments when past/present collapse, community-led resistance to displacement, technologies being used for collective memory. What signals are you tracking in your work? Submit yours and I’ll feature them in future newsletters — building a collective intelligence around these questions.

If you want to stay in the loop:

More SURROUND SOUND events coming. More methods being tested. Reply to get on the list, or just subscribe if you haven’t already.

P.S. This is the first in what will become a series of “Methods for Finding Each Other”— frameworks I’m testing for creating conditions for connection in a world that produces isolation. Future posts will dig deeper into specific methodologies: deep listening across archives, designing for co-investigation, making research practice visible without performing. If there’s a particular method you want to see unpacked, let me know in the comments.

thank you for your stewardship